The ocean needs you! With close to 100,000 hours of archived video footage⎯and more being continuously captured by Ocean Networks Canada’s (ONC) underwater cameras⎯you can help scientists answer important questions about the ocean. Play a fun video game that analyzes the behaviour of deep sea marine life.

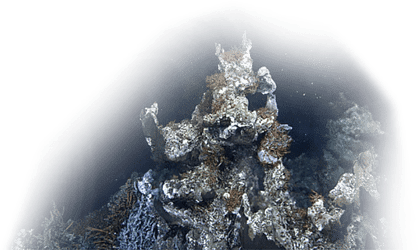

How are changes in the upper ocean affecting the abundance of organic matter⎯food for deep sea marine life⎯on the ocean floor? How do seasonal variations in oxygen concentration affect flora and fauna in Barkley Canyon, off Canada’s west coast? As a citizen scientist, you can help ONC researchers study species diversity, distribution, and behaviour in this complex ecosystem (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Organisms living in the depths of Barkley Canyon⎯such as this skate⎯have evolved to thrive in areas with high pressure, no light, and low nutrients and food availability.

ONC’s Internet-connected sensors and cameras make it possible for researchers to undertake detailed studies that further our understanding of complex ocean processes. But analyzing this relentless stream of continuous data is extremely difficult.

Enter citizen science. You can help ocean science by volunteering to become a Digital Fisher (Figure 2). Watch ONC’s deep sea video footage and count the number of animals you see. It’s simple, it’s fun and it qualifies you as a citizen scientist!

Figure 2. Digital Fishers is a fun video game that invites everyone to contribute to ocean science.

While citizen science is nothing new⎯possibly dating as far back as Galileo⎯using video data to analyze species diversity and abundance is a new field. First launched in 2012, Digital Fishers is a crowd-sourced ocean science observation game that simultaneously fulfills three important goals: monitoring deep sea marine life, developing new computer algorithms to analyze video footage, and engaging the public to help us #knowtheocean (Figure 3).

Figure 3. In 2012, a 14-year-old Ukrainian boy astonished scientists when he witnessed something never before seen on camera⎯an elephant seal eating a hagfish in Barkley Canyon (depth 890 metres).

A recent Digital Fishers campaign attracted close to 900 citizen scientists of all ages from 19 countries who made over 26,000 video annotations. This valuable volunteer contribution is helping Memorial University PhD student Neus Campanya i Llovet to identify what deep sea species⎯and how many⎯are attracted to different food sources. “This kind of research can help us understand feeding behaviours of deep sea species, in particular when used with the combination of live video cameras and citizen science campaigns,” comments Neus.

Your new citizen science challenge awaits

Launched in November 2017, a new campaign offers Digital Fishers another fun citizen science task. And this time, it’s a bit more challenging. Watch video clips to identify and count not just one, but four deep sea species: sablefish, hagfish, poachers, and eelpouts (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Your new Digital Fishers citizen science mission (should you choose to accept it) is to identify and count four deep sea species: hagfish, eelpouts, poachers, and sablefish.

“It’s a perfect outlet for wannabe scientists, from retirees to parents with children,” says Jodie Walsh, Research Coordinator at University of Victoria’s Centre for Global Studies, an organization that has been collaborating with ONC on the development of Digital Fishers with funding from CANARIE since 2012. “They’re all learning about the ocean, and doing something meaningful at the same time.”

“I like to think that I can make a contribution, albeit a small one, by participating in this project and I have the time and resources to do so,” comments citizen scientist and Digital Fishers super-user Harold Smith, a retired United States Federal Government employee and military serviceman.

Humans are expert observers

Did you know that volunteer observers are as reliable as trained researchers, and even out-perform computer algorithms? A recent ONC study explored the question of whether the crowd is as good as an expert at the simple task of counting sablefish. Over 500 Digital Fishers helped answer this question, which was published in a scientific paper Expert, Crowd, Students or Algorithm: who holds the key to deep-sea imagery ‘big data’ processing? (Matabos et al., 2017). ONC found that crowd annotators performed as well as the expert biologist. In other words, citizen science is an extremely valuable tool for analyzing large, complex datasets.

Beat the expert and the computer by following instructions

This new study explores whether citizen science performance can be further improved through specific instructions as to how species should be identified and counted. As a Digital Fisher, your contribution to science will be enhanced by following a few simple but important instructions:

1. Watch each clip for its entire length and pause it any time you see a **new fish** enter the frame. While paused, create an annotation for the new fish you have observed.

2. A fish should only be identified and counted when:

- EITHER the entire fish is in the video frame regardless of its orientation to the camera

- OR its head and at least one of its eyes is visible. For example, if you only see the tail of the fish, you should not count it, even if you strongly suspect it is a sablefish, for example.

3. Note: any fish that are visible at the start of the video are considered to have entered at the first frame and should be annotated at the beginning of the clip.

4. Keep in mind that a fish might leave and re-enter the frame. You should annotate it each time it enters even if you suspect it might be the same fish.

5. At the end of the video, create an annotation with the total count of fish of each species that you saw in the whole video.

Citizen annotations will be compared with an expert biologist and several specially-designed computer algorithms. The data collected in this campaign has the potential to be used in the analysis of species diversity (how many different species are present in a given region) and abundance (how many individuals of a species inhabit the region). The results from this study will also contribute to understanding the applications and limitations of crowd and automated analysis of stationary camera data for population studies.