Whales may be the largest animals on earth, but what happens after they die still remains something of a mystery: even the name given to their deaths — “whale fall” — evokes a sense of the unknowable. But the latest Fine Arts graduate student to be named Artist-in-Residence with Ocean Networks Canada is seeking to both explore and de-mystify the unique relationship between a descending whale carcass and the countless species that will spend decades feeding on the biomass.

“Imagine you build a new apartment building and various people live there as it ages and eventually falls apart,” notes current Department of Writing MFA candidate Neil Griffin. “That’s what happens with a whale carcass: various scavengers and decomposers move in and out . . . there are even worms that take hundreds of years to burrow single-mindedly through a thick whale vertebrae to get to the marrow inside.”

As the fourth Artist-in-Residence (AIR) with Ocean Networks Canada (ONC) — a continuing partnership with Faculty of Fine Arts graduate students that has engaged previous AIRs Colin Malloy (School of Music), Dennis Gupa (Theatre) and Colton Hash (Visual Arts) — Griffin will be fusing the creative with the scientific in a series of lyric essays titled Whale Fall, which will explore the ecological stages of whale decomposition from its last breath to its incorporation into the deep-sea ecoscape.

Fortuitously, Griffin’s proposal also lines up with ONC’s own multi-year project, Life After Death: Whale-fall Succession and Bone Decomposition Under Varying Oceanographic Conditions. Led by staff scientist Fabio De Leo and ONC Research affiliate Craig Smith, one part of this project will see a whale carcass deployed in 2025 at 890 metres off Vancouver Island under low-oxygen conditions, where it will be continuously monitored for three years with high resolution video and sensors.

“It’s a fairly new field, but some of the best minds thinking about it are right here,” notes Griffin.

Talking about science

Griffin — a trained biologist who spent a decade with the University of Calgary studying wildlife in the likes of Belize, Honduras and East Africa — sees a direct connection between his previous fieldwork and his current graduate work. His MFA thesis, for example, is The Museum of Ruin, a SSHRC-funded book-length essay exploring the biological and human history of extinction. The Tyee also recently published his essay, The Riddle of the Monkey Puzzle Tree, a fascinating conjunction of history, colonialism and natural science.

“All of my writing comes out of the tenants of wildlife biology: being the observer, trying to synthesize what you see together with what you think afterwards,” he explains. “These two fields of knowledge that we keep so far apart have at their shared core the same interest in raising up the depths and exploring the unknown—be that the psyche for the arts or the natural world for the sciences. When I saw there was a residency looking for that, it seemed right up my alley.”

Indeed, Griffin sees his ONC Whale Fall project as a natural extension of his thesis. “There’s enough connection for it to be relevant: the deep sea is also threatened by our incessant extractive activities, so there’s a lot of overlap in thought and material.”

New project, old interest

Griffin has been fascinated with the idea of whale falls since he first ran across mention of the phenomenon at the Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre during his biological studies.

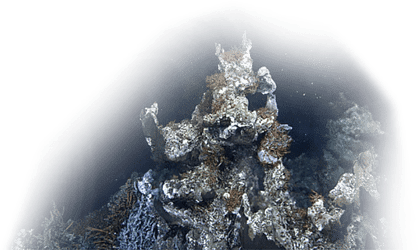

“I was looking through some journals and found these grainy, almost horror-footage photos of whale falls,” he recalls. “There were pictures of a decomposing whale carcass on the ocean floor and the weird, weird animals that were eating it: hagfish, lampreys . . . these bizarre denizens of the depths that have adapted to this incomprehensibly difficult ecosystem to live in. They’re just waiting for this bounty . . . every time a whale fall comes down to them, this desert-like environment becomes a major hotspot of activity by a massive community of animals.”

While human history is inextricably connected to the oceans, Griffin notes that all we traditionally know of the deep sea is what got “spat up” on the shores. It wasn’t until the late 19th century that we started to literally look deeper into the oceans, an exploration ONC continues to this day.

“I’ve always been interested in our relationship with the unknowable,” he notes. “What’s going on down there? It’s deep and dark and cold and mysterious and frightening . . . but also exciting. It’s such a rich vein of human imagination, and the lyric essay is a useful form for exploring all that. As a hybrid form of essay and poem, it allows me to combine a whole bunch of voices, which will give me a way to include not only science and interviews but also weave in ideas about the history and representation of the deep sea.”

Ultimately, Griffin feels his Whale Fall project is an ideal opportunity for him. “It’s a different skill set to talk about science than it is to do science. How do I make this into something people can latch onto, that makes them both excited and interested?”

He pauses and offers something of a mysterious smile. “I don’t know exactly what that would look like, but I’m excited by the possibilities of finding out.”

Follow Neil Griffin on Twitter: @prairielorax

The Artist-in-Residence program is a partnership between UVic’s Faculty of Fine Arts and Ocean Networks Canada, with additional financial support provided by the Faculty of Science and the University of VIctoria’s Office of Research Services. This continuing program strengthens connections between art and science that broaden and cross-fertilize perspectives and critical discourse on today’s major issues, such as environment, technology, oceans, cultural and biodiversity, and healthy communities. This program is open to all current University of Victoria graduate students who have completed most of their course requirements in the Faculty of Fine Arts with practice in any visual, written, musical or performance media. The next call for artists will be in Fall 2023.