An interview with Dr. Katleen Robert

As we plunge into a pivotal new decade for the health of our planet, philosopher Soren Kierkegaard reminds us that the key to moving forward is to understand our past. Ocean Networks Canada’s (ONC) tenth anniversary in the deep sea is a poignant opportunity to look at the past, present and future of ocean observing, as seen through the eyes of an emerging ocean science leader whose promising career began with the launch of ONC’s NEPTUNE network in the northeast Pacific Ocean.

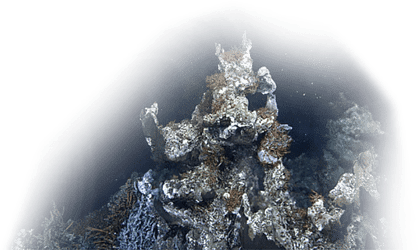

The NEPTUNE infrastructure is an 840 km loop of fibre optic cable with five nodes, each instrumented with a diverse suite of sensors that enable researchers to study interactions among geological, chemical, physical, and biological processes that drive the dynamic earth-ocean system over a broad spectrum of oceanic environments.

A decade ago, Canada made history when NEPTUNE—the world’s largest and most advanced undersea observatory according to Popular Science—ushered in a new era of ocean science. On 8 December 2009, ONC successfully connected an 800 km loop of fibre-optic cable across the Juan de Fuca plate, bringing power and Internet to thousands of sensors and instruments on the northeast Pacific seafloor. For the very first time, this pioneering installation provided long-term continuous real-time monitoring of ocean processes and events.

In 2011, Dr. Katleen Robert made history by becoming the first graduate student in the world to complete her degree using ONC’s NEPTUNE deep sea laboratory as her primary research tool. Pioneering the use of remote-controlled video cameras during her Masters degree, a decade later she is Assistant Professor and Canada Research Chair at the Fisheries and Marine Institute of Memorial University, Newfoundland, and a member of ONC’s Observatory Council. We sat down with Katleen to talk about her ocean science career, NEPTUNE’s early days, and the future of ocean observing.

ONC: What originally attracted you to work in ocean science?

Katleen Robert (KR): Growing up, I always wanted to be an ocean scientist. I discovered seafloor mapping during a NEPTUNE expedition. We were doing remotely operated vehicle mapping to lay the first instrument cables at Endeavour and I was amazed at how few people knew how to do this. They were creating beautiful high-resolution maps and that’s when I realized that this is what I want to do.

ONC: How did you get involved with NEPTUNE during your Masters degree?

KR: When I arrived at the University of Victoria (UVic) in January 2009, NEPTUNE was still a skeleton of fibre-optic cables. I was working with ONC’s chief scientist Kim Juniper studying ecological processes occurring in deep sea habitats. The NEPTUNE instruments were going out a few months later so I got the opportunity to join the expedition and actually be involved with deploying most of the equipment for the first time. Being part of the expeditions that helped bring NEPTUNE online was one of the highlights of my time at UVic.

Katleen Robert onboard Research Vessel Thomas Thompson during the 2009 expedition to complete the deployment of NEPTUNE extension cables and instruments. (Photo credit: Katleen Robert)

ONC: What was it like to be onboard the RV Thomas G. Thompson for the very first deployment of NEPTUNE instruments into the deep sea?

KR: A lot of this was being done for the first time so there was a bit of a learning curve. I was working with the remotely operated vehicle operators to ensure the extension cables would be laid properly. We had to problem solve on the spot and pay attention to every little detail, like tying little pieces of jute rope through each layer of cable to give just enough tension to help lay out the cable. The level of detail necessary for things to run smoothly was quite impressive.

ONC: The real-time continuous data provided by NEPTUNE has been described as “a new way of doing science”. What did this cabled ocean observing infrastructure make possible?

KR: It was exciting how much data could be collected so quickly and how one could actually interact with the instruments, monitor things in real time and actually adapt the sampling scheme to events happening in real-time. This ability for continuous long-term time series data was really new. Being able to remotely turn the underwater camera on in the lab, and pan and zoom on a particular organism that was there right now made it much more interesting.

ONC: What was the response from the science community when you presented your NEPTUNE research?

KR: There was a lot of amazement at the volume of data coming through. Especially with video data. Ten minutes of video might take from 30 minutes to three hours to actually analyze. So the big question was how are we going to handle all these data?

ONC: What was the most challenging aspect of using the NEPTUNE cameras to gather data for your research?

KR: One of the big challenges was that there was no automated program to operate the camera. I was studying bioturbation, which is how organisms move sediment and I was trying to track sea urchins moving through the field of view. I needed to have the camera on every two hours, so for a stretch of a couple of days, I had a timer and every two hours I would turn the camera on. It could only be operated from this one computer so I slept in the lab and I would wake up every two hours to turn on the lights and the camera. Shortly after that the ONC team wrote a program to automate data collection.

Becoming an Ocean Scientist: "The deep sea has this mystery, this appeal, and that's really what got me.” In this 2011 video, Katleen Robert describes her excitement for studying deep-sea biology via remote video.

ONC: ONC has been gathering deep sea data for a decade now. How does 10 years of continuous deep sea data help researchers understand the ocean and our changing planet?

KR: It’s starting to be a long enough amount of time to establish a baseline and start to see how things might be changing. Cabled observatories give us the high-resolution temporal data needed to better understand a suite of ecological drivers and how ocean change may affect ecosystems. Monitoring significant events like The Blob occurring in real-time make cabled observatories very exciting.

“Katleen Robert’s Masters using NEPTUNE data was the first step in a very rapid professional rise to become probably one of the youngest people in the country to step into a Canada Research Chair. Her career serves as an example for future ocean science researchers in the next decade - there is so much opportunity for innovative creative determined pioneers to apply their ocean tech and data skills to save the planet.” - Kim Juniper, Chief Scientist, ONC

ONC: What research are you working on now as Canada Research Chair at Memorial University?

KR: My research right now is mostly related to seafloor and habitat mapping. My team do acoustic surveys to get the depth of the seafloor and combine this with drop-camera videos to look at species distribution. These data are used to understand species-environment relationships, habitats characteristics and how species may respond to ocean change.

ONC: In 2019 you joined ONC’s Ocean Observing Council. How is ocean observing continuing to evolve and what do you see happening in the next decade?

KR: Over the last decade ONC has deployed community observatories in the Arctic and along the British Columbia coast, and now ONC is building a small observatory in Newfoundland in collaboration with the Fisheries and Marine Institute of Memorial University. Extending our knowledge of the ocean to many more areas will be crucial. Personally, I see coupling automation with cabled observatories has significant potential. Using underwater robots, called autonomous underwater vehicles (AUV), we will soon be able to survey an area in high resolution, and have the AUV visit a docking station to recharge and download the data, before going on to do another survey. We’re already starting to see this with gliders.

I’m also looking forward to the implementation of artificial intelligence and machine learning in data processing. We’re collecting large amounts of data more quickly and we will need help from computer scientists to detect events automatically or recognize individual species in videos.

Ocean science is an exciting field with a lot of opportunity, especially in the technology sector so it’s a great career for young scientists to work towards.

Our thanks to Dr. Katleen Robert for taking the time out of her busy life to talk with us. We look forward to checking in with her again in 2030, to review what we have collectively learned and achieved during the UN Decade of the Ocean (2021-2030) as we look forward into the 2030’s and beyond.

> “Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.” Soren Kierkegaard